Abstract

Background: Although neonates are reported to be at greater risk of medication error than infants and older children, little is known about the causes and characteristics of error in this patient group. Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) is a technique used in industry to evaluate system safety and identify potential hazards in advance. The aim of this study was to identify and prioritise potential failures in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) medication use process through application of FMEA.

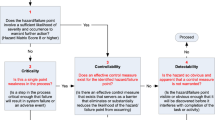

Methods: Using the FMEA framework and a systems-based approach, an eight-member multidisciplinary panel worked as a team to create a flow diagram of the neonatal unit medication use process. Then by brainstorming, the panel identified all potential failures, their causes and their effects at each step in the process. Each panel member independently rated failures based on occurrence, severity and likelihood of detection to allow calculation of a risk priority score (RPS).

Results: The panel identified 72 failures, with 193 associated causes and effects. Vulnerabilities were found to be distributed across the entire process, but multiple failures and associated causes were possible when prescribing the medication and when preparing the drug for administration. The top ranking issue was a perceived lack of awareness of medication safety issues (RPS score 273), due to a lack of medication safety training. The next highest ranking issues were found to occur at the administration stage. Common potential failures related to errors in the dose, timing of administration, infusion pump settings and route of administration. Perceived causes were multiple, but were largely associated with unsafe systems for medication preparation and storage in the unit, variable staff skill level and lack of computerised technology.

Conclusion: Interventions to decrease medication-related adverse events in the NICU should aim to increase staff awareness of medication safety issues and focus on medication administration processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Smith J. Building a safer NHS for patients: improving medication safety. Department of Health, UK [online]. Available from URL: http://www.doh.gov.uk/buildsafenhs/medicationsafety/ [Accessed 10 Feb 2004]

Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med 1991; 324(6): 377–84

Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust 1995; 163(9): 458–71

Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, et al. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals: principal findings from a national survey. Occasional Paper No. 3. Wellington: Ministry of Health [online]. Available from URL: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf [Accessed 2004 Jan 23]

Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, et al. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals: I: occurrence and impact [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/1151167/271 [Accessed 2005 Feb 8]

Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. BMJ 2001; 322(7285): 517–9

Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1997; 277(4): 307–11

Conroy S. Paediatric pharmacy: drug therapy. Hosp Pharm 2003; 10: 49–50, 54, 56-7

Conroy S, McIntyre J, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999; 80(2): F142–4

Koren G. Therapeutic drug monitoring principles in the neonate. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. Clin Chem 1997; 43(1): 222–7

Zeroing in on medication errors. Lancet 1997; 349 (9049): 369

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 2001; 285(16): 2114–20

Vincer MJ, Murray JM, Yuill A, et al. Drug errors and incidents in a neonatal intensive care unit: a quality assurance activity. Am J Dis Child 1989; 143(6): 737–40

Williams E, Talley R. The use of failure mode effect and criticality analysis in a medication error subcommittee. Hosp Pharm 1994; 29(4): 331–2

Cohen MR, Senders J, Davis NM. Failure mode and effects analysis: a novel approach to avoiding dangerous medication errors and accidents. Hosp Pharm 1994; 29(4): 319–30

Schneider PJ. Applying human factors in improving medication-use safety. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002; 59(12): 1155–9

Raju TN, Kecskes S, Thornton JP, et al. Medication errors in neonatal and paediatric intensive-care units. Lancet 1989; II(8659): 374–6

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995; 274(1): 29–34

Spath PL. Using failure mode and effects analysis to improve patient safety. AORN J 2003; 78(1): 16–37

Perlstein PH, Callison C, White M, et al. Errors in drug computations during newborn intensive care. Am J Dis Child 1979; 133(4): 376–9

Pepper GA. Errors in drug administration by nurses. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1995; 52(4): 390–5

Fontan JE, Maneglier V, Nguyen VX, et al. Medication errors in hospitals: computerized unit dose drug dispensing system versus ward stock distribution system. Pharm World Sci 2003; 25(3): 112–7

Fortescue EB, Kaushal R, Landrigan CP, et al. Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111(4 Pt 1): 722–9

Cousins D, Clarkson A, Conroy S, et al. Medication errors in children: an eight year review using press reports. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther 2002; 5(2): 52–8

Wilson DG, McArtney RG, Newcombe RG, et al. Medication errors in paediatric practice: insights from a continuous quality improvement approach. Eur J Pediatr 1998 Sep; 157(9): 769–74

Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE, et al. Medication error prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children’s hospitals. Pediatrics 1987; 79(5): 718–22

Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, et al. Variables associated with medication errors in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatrics 2002; 110(4): 737–42

Lesar TS, Briceland LL, Delcoure K, et al. Medication prescribing errors in a teaching hospital. JAMA 1990; 263(17): 2329–34

Ross LM, Wallace J, Paton JY, et al. Medication errors in a paediatric teaching hospital in the UK: five years operational experience. Arch Dis Child 2000; 83(6): 492–7

Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ 1998; 316(7138): 1154–7

Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995; 274(1): 35–43

Runciman WB, Edmonds MJ, Pradhan M. Setting priorities for patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11(3): 224–9

Marx DA, Slonim AD. Assessing patient safety risk before the injury occurs: an introduction to sociotechnical probabilistic risk modelling in health care. Qual Saf Health Care 2003; 12Suppl. 2: II33–8

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a fellowship awarded to Desireé Kunac by the Child Health Research Foundation of New Zealand. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kunac, D.L., Reith, D.M. Identification of Priorities for Medication Safety in Neonatal Intensive Care. Drug-Safety 28, 251–261 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528030-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528030-00006